Tera Pruitt

University of Cambridge

First version submitted for Masters in Crime and Thriller Writing on 20 March 2022

Updated in 2024 for references

Engaging the Science of Storytelling in Crime and Thriller Stories:

Why Certain Story Structures Offer More Impact for the Reader

This paper examines one aspect of crime and thriller writing—story structure—by exploring why some story structures are more powerful and memorable than others. Engaging with multidisciplinary research from neuroscience, psychology, criminology, philosophy, and literary criticism, this essay follows peer-reviewed research by the author (Pruitt, 2022), arguing that certain storytelling structures satisfy readers by aligning with the way the brain processes information. This paper presents two evidence-based story structure fundamentals that powerfully engage readers, alongside a close comparative analysis of five literary texts. While this essay’s thesis applies to essentially all stories, this close examination of story structure is of particular interest to crime and thriller writing—one of the most commercial literary genres. Crime and thriller writers typically aim to produce exciting ‘page-turners’ that engage readers in suspenseful plots; thus, the genre has a particularly keen interest in understanding what structures best hook readers and translate into book sales.

Thesis and Literary Context

This essay is critically situated within a burgeoning form of critique: the ‘scientization’ of literature and the study of how the human body is intimately involved in the production and consumption of literary text (Wilson, 2022). While literary critics have quite rightly debated how much biology we can—or should—inject into literary criticism (Kornbluh, 2020), the ontology of the matter is clear: human brains produce literary texts, and human brains consume those texts. This incontestable fact about the requisite interaction between human bodies and literature yields the simple question: how does the human brain affect the production and consumption of fiction?

While an entire dissertation could be written on this subject, this paper focuses on just one topic: understanding the science of why human brains crave structure, and how that translates to satisfying crime and thriller stories. Alongside multidisciplinary research, this paper examines two simple story fundamentals:

(1) a beginning, midpoint, and ending;

(2) a thesis, antithesis, and synthesis.

The essay then offers a close reading of how these fundamentals operate in five comparative crime and thriller texts. Much like in Music Theory, where the musical profession advocates musicians should first understand classic artistic structures (e.g., octaves, stanzas, verse-chorus-bridge arrangements, etc.) and why they work, before then attempting experimental music composition, this paper argues the professionals who produce crime and thriller writing should first understand why certain classic story structures work before experimenting and breaking the rules.

The Science of Storytelling

While the concept of ‘storytelling’ is most often associated with pure fun and entertainment, recent multidisciplinary research challenges this ‘fluff’ association as a misconception. Far from being fanciful or unproductive, a story is an essential biological tool humans use to deliver and process important information (Cron, 2012, p.9; Wilson, 2005, p.ix). Lisa Cron summarises this line of research, arguing our brains are neurochemically hardwired to consume stories:

Story was more crucial to our evolution than our opposable thumbs, because all opposable thumbs did was let us hang on. It was story that told us what to hang onto… Stories feel good for the same reason food tastes good, because without it, we couldn’t survive. (2014)

Pleasurable storytelling developed alongside other critical biological features of the human body: “These rewarding states of mind seem so natural to us…[but] would not be possible unless the mind contained elaborate reward systems that produced them in response to some stimuli and not others” (Tooby and Cosmides, 2001, p.8). Steven Pinker calls this aesthetic pleasure evolutionary “cheesecake” (1997), and agrees that stories may biologically function as “experiment-driven learning” (2007). Essentially, stories biologically operate as a way of rehearsing possible future outcomes, increasing our chances of survival in the future if we encounter a situation similar to the one in the story (Gottschall and Wilson, 2005). Good stories induce a proxy for immediate experience: a sense of ‘almost being there’ that allows consumers to learn almost as if they had gone through the events themselves. In this evolutionary model, a non-fiction story told by a colleague about what happened when they crashed their car running a red light is as salient as a fictional story told by a driving instructor about what misfortune might happen if you run a red light. Both stories improve your chances of surviving your next car journey.

MRI scans and studies of the brain demonstrate that stories are more effective at delivering information than presenting strings of facts (Speer et al., 2009; Zak, 2013). While engaged in a good story, our brains light up as if we ourselves are doing the activity described (Speer et al., 2009), and we are flooded with oxytocin and dopamine (Zak, 2014, 2015). Neuroscience experiments suggest that when a presentation is delivered in a story format, it results “in a better understanding of the key points a speaker wishes to make and enable[s] better recall of these points weeks later” (Zak, 2014). The biomechanical reason is simple: when a story is told well, our body is flooded with reward hormones and our brains engage in ‘practice’ motor skills—something that does not happen when information is delivered as a series of facts (Zak, 2020). In other words, stories invest us in the information being delivered.

This is great news for storytellers like crime and thriller writers, who need to invest readers in their stories. However, a story must be told effectively for an audience to receive these cognitive benefits. In experiments in the lab, narrative information with the same characters delivered in a “flat structure” rather than a “typical story form” did not deliver the same cognitive benefits to its audience (Zak, 2015). In other words, stories that use classic structural conventions resonate the most with readers. When stories are arranged in different narrative structures, readers are far less neurochemically invested.

Background: Crime and Thriller Case Studies

Two simple evidence-based structural rules go a long way towards producing an impactful story with cognitive benefits. These two structural fundamentals will first be examined in depth in the next section, before being analysed in the context of five crime and thriller texts, including: three short stories (two follow conventions, one does not), and two recent novels by the same author (one follows conventions, one does not). All five stories were selected for analysis because of their aesthetically beautiful and competent writing.

The short story The Unsolved Puzzle of the Man with No Face by Dorothy Sayers (1958) offers aesthetic language and a high-concept pitch: a puzzling murder on a beach and a gentleman detective’s attempt to solve the crime. There is nothing ostensibly wrong with the story. In fact, The Unsolved Puzzle has been a productive text for literary critics, especially in discussions on the history of crime fiction (Bavidge, 2022). However, The Unsolved Puzzle is far less memorable and popular than other comparable stories. For example, The Lottery by Shirley Jackson (1946), which tells the story of a lottery turned deadly, was written around the same time, yet is still one of the most-read short stories today (Overbey, 2019). Another crime and thriller short story, The Cask of Amontillado by Edgar Allen Poe (1846), has been described as “one of the world’s most perfect short stories” (CliffsNotes, 2022) and is still extremely popular 176 years after it was written. This paper considers whether the structural shortcomings of The Unsolved Puzzle contribute to its lack of popularity compared to other stories of a similar calibre.

This essay also explores structural choices in longer crime and thriller fiction through a comparative analysis of two recent novels by the same author, Paula Hawkins: The Girl on the Train (2015) and Into the Water (2017). Both novels have aesthetically beautiful writing and offer a high-concept crime and thriller pitch. However, Hawkins’s first novel, The Girl on the Train—about an alcoholic who witnesses a crime—was a massive success. Hawkins’s second novel Into the Water—about the murders of women who drowned in the same pond—was far less successful and panned by critics (BookMarks, 2022). This paper argues story structure was integral to why Hawkins’s first novel was more successful than her second.

Storytelling Fundamentals in Context

The second half of this paper presents the multidisciplinary research behind two simple structural rules—(1) a beginning, midpoint, and ending; (2) a thesis, antithesis, and synthesis—then analyses these structures in the context of all five example stories.

Fundamental 1: Beginning, Midpoint, Ending

The first structural fundamental: a compelling story must have a clear beginning, middle and end—a rule that harks back to Aristotle’s Poetics (1996). Before we collectively roll our eyes at how simple this advice sounds, consider how many narratives do not do this. The middle is often forgotten. Instead, many writers focus on creating strong openings and powerful climaxes—then leave the middle as episodic chapters that attempt to compel the reader to reach the end. Unfortunately, that is not a true middle. Instead, a structurally sound story contains a focal point in the middle that is as important as the beginning and the end. This conceptual middle often—but not always—falls directly in the middle of a text’s word count. In fiction, this key moment is called a midpoint and is usually found in bestselling movies, television episodes, and novels (Yorke 2013, p.37).

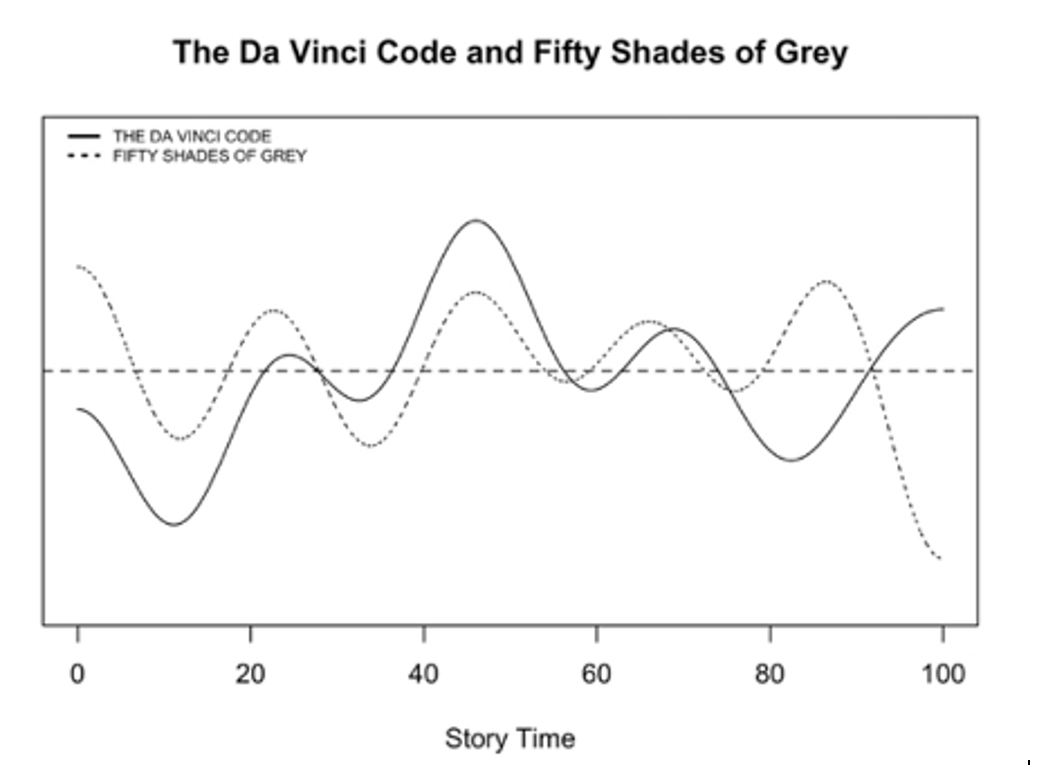

Biologically, this simple structure helps our brains receive and process information. In neuroscience experiments on attention, audiences did not respond as well when they consumed information in a ‘flat’ presentation with less focused structure: “People who watched this [flat] story began tuning out mid-way through…Measures of physiological arousal waned…” (Zak, 2013). Adding a midpoint gives the reader an important cognitive waypoint before heading down the other side of the story. The midpoint maintains attention and drives the story action forward. This beginning, midpoint, and ending structure has also been quantitatively observed by data scientists. Researchers from Stanford University’s Literary Lab have created algorithms using word analysis to visually graph over 20,000 novels, demonstrating that effective story structures follow a “three-act structure, midpoint, and the difference between the beginning and the end” (Archer and Jockers, 2016, p.95). When researchers plotted bestselling stories, they found patterns of clearly defined openings, midpoints where the plot turned, and defined endings (Ibid, p.105-106). Research suggests that a midpoint is one of—if not the most—important parts of a successful story. In top global bestsellers, including The Da Vinci Code (Brown, 2009) and Fifty Shades of Grey (James, 2012), the midpoint represents a defined moment of action that peaks at some of the highest levels of tension in the story (Archer and Jockers, 2016, p.106).

Figure 1. Clearly defined midpoints appear in top thriller bestsellers (Archer and Jockers, 2016, p.106)

Analysis of Fundamental 1 in Crime and Thriller Stories

This first structure fundamental is visible in our five comparative crime and thriller texts. The two popular short stories The Lottery (Jackson, 1946) and The Cask of Amontillado (Poe, 1846) both contain striking structural beginnings, midpoints, and endings. The same is true of the bestselling novel The Girl on the Train (Hawkins, 2015). However, this is not the case for the less popular stories in this case study: the short story The Unsolved Puzzle of The Man with No Face (Sayers, 1958) and the novel Into the Water (Hawkins, 2017).

The Lottery opens with the clearly defined moment when “The people of the village began to gather in the square” (p. 3) for the town lottery. This beginning is followed by a clearly defined midpoint, exactly in the middle of the text: “A sudden hush fell on the crowd” (p. 11) when the lottery begins. The ending takes place in the last paragraph of the story when Tessie “wins” the lottery and is stoned to death (p. 19). Similarly, the revenge thriller The Cask of Amontillado offers a defined beginning, midpoint, and ending. The beginning occurs when narrator Montresor meets his victim, Fortunato: “It was about dusk, one evening during the supreme madness of the carnival season, that I encountered my friend” (p. 1). In the middle of the story, Poe presents a midpoint where the two men stand “together on the damp ground of the catacombs” (p. 5). At this moment, Montresor offers Fortunato one last chance to leave; however, his greedy victim “again took my arm, and we proceeded” (p. 7) into the deadly catacombs. Tension builds as Montresor leads Fortunato through the cavernous crypt and chains him to a wall. At the defined ending, Montresor “began to vigorously wall up the entrance of the niche” (p. 13) where he has chained Fortunato, and the story resolves when Montressor leaves him to die.

Similarly, Paula Hawkins’s celebrated novel The Girl on the Train also has a defined beginning, midpoint, and ending. The beginning—the inciting incident—occurs when Rachel goes to see the partner of a woman she’s been spying on from a train, but blacks-out after witnessing a crime; she wakes up the next morning knowing that “Something is wrong” (p. 61). The midpoint appears almost exactly midway through the word count, when Rachel learns the missing woman has been murdered, which is “so much worse than I imagined” (p. 213). The ending occurs at the climax, when Rachel realises her ex-husband Tom murdered the woman: “There was nothing I could do. I had to finish it” (p. 393). These clearly defined plot points drive the story forward.

In contrast, Sayers’s short story The Unsolved Puzzle does not have a defined beginning. The inciting incident—the introduction of a puzzling murder—is first discussed by a variety of people on a train. While this is a fun way to introduce a murder, it grows a bit unwieldy when it takes several pages before the reader is fully aware of which character is meant to be the protagonist and/or detective. By the time the police Inspector finally discusses the crime with protagonist Lord Wimsey on page 7, confirming the key players of the actual story, the action has meandered into a somewhat sloppy middle. The structural timing of when the protagonist first seeks to prove his theory sits well past the beginning of the plot. The story does present a midpoint: midway through, Lord Wimsey sees a portrait of the murder victim and discovers the victim’s co-workers hated him. While this is a nice moment, its impact falls short when the revelation is felt by a different character from the protagonist: ‘“Oh!” said Hardy, a little surprised…The portrait seemed to sneer at his surprise”’ (p. 10). By placing the moment of impact on the shoulders of another character—structurally keeping the reader at a distance from the protagonist they are rooting for—the power of the midpoint is weakened. The story also does not have a clear ending. The climax occurs when Lord Wimsey presents his version of events to the police; however, the Inspector contradicts his version with another that includes a confession. Readers are left broadsided by the sudden penultimate line: “‘What is Truth’? said jesting Pilate” (p. 18). While this literary choice is intentional, and while such uncertainty may be enjoyable to some readers, it is overall less structurally satisfying than if the story had offered a defined ending with a clear conclusion.

Paula Hawkins’s second novel, Into the Water, likewise falls short in its structural approach, starting with no clear beginning. Technically, the inciting incident of Into the Water is supposed be the drowning of a woman named Nel. However, Hawkins soon undermines this apparent opening with cyclicality, weaving in previous character deaths and eventually telling the reader the story is not, in fact, about Nel at all:

“All this—your Nel—it’s not about poor Katie Whittaker or that silly teacher or Katie’s mum or any of that. It’s about Lauren, and Patrick.” (p. 329)

“It’s Lauren you’re looking for, she’s the one who started all this!” (p. 377).

The book cover claims the inciting incident is Nel’s death, but her story gets hijacked by Katie’s more interesting suicide, then pivots to actually being about the murder of Lauren. The reader is lost. In total, the story presents 11 different viewpoints and character arcs, as well as multiple crimes with unclear connections, resulting in no definitive through-line. Reviewers lament: “I was so disconnected with this story that it just wasn’t enough to save this for me.” (Lyons, 2017). Without a clear beginning to establish a structural story to hang onto, readers are left scratching their heads and wondering: what should I care about?

The novel also has no midpoint, just multiple reveals in the general vicinity of the middle. Major plot revelations occur on pages 113, 158, 216, 287, 300, 311—some of these about rape, paedophilia, illicit relationships, and possible revelations about who murdered whom. However, no one revelation is structurally important enough to be a midpoint. Perhaps Hawkins had already undermined her structural possibilities for a defined midpoint, since the story has no clear protagonist and no clear main victim. Ultimately, the novel suffers from no defined ending either. Eventually a character named Patrick announces to a police officer that he killed Nel—“I threw her over” (p.396)—which suggests closure—except the story then quickly asserts that it is never-ending:

“I felt as I’d been feeling for a while: that all this, Nel’s story and Lauren’s and Katie’s too, it was all incomplete, unfinished. I never really saw all there was to see.” (p. 415)

The ‘real’ ending appears in the very last line, when Sean says: “With my hands in the small of Nel’s back, I pushed her away” (p.426), insinuating that it was Sean and not Patrick who murdered Nel. By this time, all the air has been let out of the balloon by another cheap trick. This double ending with an assertion of ‘neverendingness’ winds up as a double negative for the reader—cancelling out any impact. While Into the Water offers beautiful language and haunting atmosphere, the structure is cyclical and disordered. Critics panned the book, and even Val McDermid concluded in her review that she suspected book sales would be much higher than reader enjoyment (McDermid, 2017; BookMarks, 2022).

While stories like Into the Water and The Unsolved Puzzle arguably present a free-spirited, ‘experimental’ approach to storytelling, the problem with such untethered interpretation becomes quickly apparent: a lack of basic structure displaces trust between the author and the reader. Experimentation must still be done with intent. Without an underpinning beginning/middle/end, offering readers a basic guiding framework, stories like Into the Water quickly fall apart. In stories that comes close but fall just short—like The Unsolved Puzzle—the story remains somewhat enjoyable but far less impactful and memorable than comparable stories like The Cask of Amontillado and The Lottery. Neuroscientists have found a direct connection between well-structured stories and trustworthiness (Lin et al., 2013; Zak, 2014). The reverse is true too. Without basic structure, writers run the risk of losing the engagement and trust of their audience. A reader trusts the author to be moving a compelling story forward. Poor structure undermines that trust and leaves an audience feeling vulnerable: an educated audience may walk away feeling frustrated by the lack of narrative coherence; a less confident audience may feel they are missing something or worry they lack the ability to understand.

Fundamental 2: Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis

The second structural fundamental of storytelling is to present a thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. While more abstract in nature, this structural fundamental is no less important to a well-told story. Referred to as the Hegelian dialectic, the thesis/antithesis/synthesis model:

“postulates (1) a beginning proposition called a thesis, (2) a negation of that thesis called the antithesis, and (3) a synthesis whereby the two conflicting ideas are reconciled to form a new proposition.” (Schnitker and Emmons, 2013)

Storytelling experts argue the “three-act” structure whose action hinges on a thesis/antithesis/synthesis is the most enduring pattern, endlessly repeated by the most impactful and memorable stores (Yorke, 2013). Playwright David Mamet claims this pattern “is an organic codification of the human mechanism for ordering information” (qtd. in Yorke, 2013, p.28). John Yorke argues this structure is “at the heart of the way we perceive the world” (2013, p.29). In classic storytelling, this Hegelian framework often appears in the process of a character overcoming their core obstacle: “Take a flawed character, and at the end of the first act plunge them into an alien world, let them assimilate the rules of that world, and finally, in the third act, test them to see what they have learned” (2013, p.28).

This pattern is also endlessly repeated by real-world humans in our everyday lives. Research from the criminal justice system has found that jurors construct stories out of evidence they hear in a trial. Trial outcomes differ when a jury is told the same evidence of a crime in no particular order versus in a “Story Model” (Pennington and Hastie, 1992). Psychologists define this Story Model as having three parts: evaluating evidence, considering alternatives, and synthesising information in a final verdict—essentially a dialectical thesis/antithesis/synthesis. In other words, telling stories in this particular structure increases their power: “The structure of stories…plays an important role in the jurors’ comprehension and decision making processes” (Pennington and Hastie 1992, p.190). This Hegelian dialectic framework is pivotal to how humans communicate and receive information.

It is no coincidence a thesis/antithesis/synthesis sits at the heart of satisfying fiction, since this is exactly how the brain processes information. Karl Friston (2010), neuroscientist and authority on brain imaging, revolutionised the study of the human brain with his ‘free-energy minimization’ model. In a paper worth reading in full, Evert Boonstra and Heleen Slagter outline how “Friston’s framework [of the brain] converges with the dialectics of Georg Hegel” (2019, p.1). The brain undergoes a continuous cyclical process of anticipating what it expects to encounter in the world, interacts with negating forces in the environment, resulting in the brain’s synthesis of information in a new anticipatory model.

Storytelling fits smoothly into this processing model. In our biological search to overcome constant deficiencies (e.g., need for food, discomfort, understanding, etc.), our brains cycle, constantly trying to synthesise our environmental and biological conditions. When confronted with new information, the mental gap between knowing and not knowing is called “cognitive dissonance” (Seel, 2012). We crave to satisfy this deficiency by finding suitable explanations. If we consider cognitive dissonance concretely in Friston’s model, this is simply how the brain works. We exist in a never-ending cycle of anticipation and processing contradiction: “It is this contradiction between habitual structure and lack, or organization and disorganization, which gives rise to the organism’s internal purpose or drive” (Boonstra and Slagter, 2019, p.7). In storytelling terms, this is referred to as the ‘narrative drive.’

Structured stories have been found to be more powerful in laboratory settings and are more widely consumed than other narrative structures (Yorke, 2013; Zak, 2014; Archer and Jockers, 2016). Not only is the Hegelian tension of contradiction central to our experience of the world as brains in human bodies, but synthesising ideas in stories offers readers an impactful cycle of discomfort followed by memorable relief, part of our never-ending cycle of understanding. In this way, stories with structural tension become impactful and memorable.

Analysis of Fundamental 2 in Crime and Thriller Stories

This second story fundamental is visible in our five example crime and thriller stories.

First, a defined thesis, antithesis, and synthesis is clearly visible in The Lottery (Jackson, 1946), most evident in the structured speech by character Old Man Warner, the oldest man in town. The story’s thesis appears in the opening as the village unquestioningly follows tradition. As Old Man Warner says, “There’s always been a lottery” (p. 13). The antithesis appears near the midpoint: humans repeat traditions out of irrational fear. Old Man Warner warns the lottery is necessary for the village’s survival:

“Pack of crazy fools... Next thing you know, they’ll be wanting to go back to living in caves, nobody work anymore, live that way for a while. Used to be a saying about ‘Lottery in June, corn be heavy soon.’ First thing you know, we’d all be eating stewed chickweed and acorns. (p. 13)

The story’s synthesis appears at the end when Tessie Hutchinson is stoned to death:

“…the villagers moved in on her. “It isn’t fair,” she said. A stone hit her on the side of the head. Old Man Warner was saying, “Come on, come on, everyone.” (p. 19)

In this moment, the story’s synthesis powerfully argues that society must re-examine its traditions. By presenting the story action in a thesis/antithesis/synthesis framework, rather than in another progression of meaning, the story’s message delivers far more impact.

Similarly, The Cask of Amontillado (Poe, 1846) is thematically told within a powerful thesis/antithesis/synthesis framework. The thesis appears at the beginning, uniquely situated in the mind of a sociopathic murderer: people who hurt others should be punished, an argument stated by Montresor in the first line: “A thousand injuries of Fortunato I had borne as I best could…I vowed revenge” (p. 1). Montresor feels he has the right to hurt someone who has injured him. Still inside the mind of a murderer, the antithesis appears at the midpoint: wrong can be redressed by taking clever revenge. Montressor cleverly pretends to care about Fortunato, offering him the opportunity to leave and not enter the catacombs, but Fortunato cannot resist temptation: “‘We will go back; you will be ill, and I cannot be responsible’…He again took my arm, and we proceeded” (p. 6-7). Montresor feels absolved of responsibility if Fortunato walks into his own death trap. The powerful synthesis hits readers at the end: vigilante revenge outside the law is unjust and evil, going too far. Readers feel horror and repulsion in the last line: may he rest in peace, “In pace requiescat!” (p. 16). Finally outside the murderer’s mind, readers receive a rush of insight about how Fortunato was left to die. Any element of justice for the wrong to Montresor is lost in the injustice of his horrific murder. By arranging the story’s structural action in a Hegelian framework leading up to a powerful synthesis at the end, the story becomes far more impactful and memorable.

Similarly in longer fiction, The Girl on the Train (Hawkins, 2015) is also arranged with a powerful Hegelian structure. The beginning presents a compelling thesis: some strangers seem to have perfect lives, in contrast to our own troubles. This thesis is stated by protagonist Rachel on the second page of the novel: “There’s something comforting about the sight of strangers safe at home” (p. 16). Near the midpoint, a powerful contradicting antithesis is presented when the perfect woman Rachel has fantasized about is found murdered: inside all those perfect-looking houses lie serious, even deadly, problems. Rachel painfully thinks at this moment, “It’s worse, so much worse than I imagined” (p. 213). The synthesis comes at the very end, when Rachel confronts her dangerous domestic abuser, resulting in a powerful understanding: justice comes from the effort to seek out truth and make things right, not in turning away from wrongdoing. After Rachel processes that she was a victim of domestic abuse—“my life with him—was an illusion” (p. 400)—she is finally set free from the past, once again able to “see faces in brightly lit windows…travellers warm and safe on their way home” (p. 402).

In contrast, both the short story The Unsolved Puzzle (Sayers, 1958) and Hawkins’s second novel Into the Water (Hawkins, 2017) fall short in their thematic structural impact. While The Unsolved Puzzle does structurally present a thesis and antithesis, the story never offers a synthesis that could increase its power. The short story’s opening line begins with a train passenger asking, “And what would you say, sir…to this here business of the bloke what’s been found down at the beach…” (p. 1). This playful thesis presents a twist on classic detective stories, directly asking the reader: can you come up with a good solution to a tricky mystery? The rest of the story presents theories of increasing likelihood, culminating in an ending that directly undermines the strongest hypothesis presented by Lord Peter. The antithesis climaxes in the penultimate line, “‘And what is Truth?’ said Jesting Pilate” (p.18). In other words, clear solutions do not always exist for complex puzzles. While this is a fun premise, the story bluntly ends on that note. It never moves beyond the antithesis. Without the opportunity to progress toward a satisfying deeper meaning, readers are robbed of the rush of insight that comes from an engaging synthesis. This structural issue may be a clue as to why the story is less popular and enduring than other short stories, despite its charms.

In longer fiction, the novel Into the Water suffers greatly from not having satisfying overarching structural tension. All suspense in the story comes from ‘micro-moments’ of revelation, such as rapid cliff-hangers at chapter endings:

“She should have never gone in. It should have been you.” (p. 43)

“I couldn’t touch her. Not after what I’d done.” (p. 161)

“I kept my promise. You didn’t.” (p. 204)

“She looked at me like I was a bit dim…It’s been happening since November” (p.221)

“Lena is Robbie Cannon’s daughter.” (p. 278)

Because these moments of revelation are untethered to a cohesive story arc, as discussed previously, the cliff-hangers become cheap tricks attached to no underpinning structure. Disappointed reviewers have called Hawkins out for “liberal use of coy suspense-building devices” (Miller, 2017) that mostly lead nowhere.

Hawkins’s previous novel, The Girl on the Train, is also a multi-viewpoint story told through the eyes of three different women, but in that book, Hawkins presents her thematic Hegelian structure within a single story: the murder of one woman. In contrast, the cyclical multiple drownings of Into the Water—some suicide, others murder, some accidental, told through 11 viewpoints—muddle any opportunity for the reader to grasp the point of the story. Early in the novel, Hawkins thematically tries to connect the drowned women by presenting the story’s thesis right upfront:

“No one liked to think about the fact that the water in that river was infected with the blood and bile of persecuted women, unhappy women.” (p. 20)

The pond in in the story represents society’s rejection of ‘difficult’ women—an engaging premise. However, contradictory themes are never subsequently presented. No alternatives are considered. An antithesis is never offered in the novel. Subsequently, readers must trudge through a meandering 426-page story about various people who are angry at difficult women, and who mostly remain angry at the end of the book. By only presenting a singular thesis, Hawkins’s readers are left without any intellectual engagement or deeper meaning. They are robbed the satisfaction that comes from the Aha! moment of a story’s synthesis—when the thesis and antithesis collide together to create new understanding. Reviewers have bitterly voiced their disappointment on this subject:

Hawkins has identified what she believes to be the heart of her nascent franchise: stories in which fragile, damaged, or otherwise disempowered Cassandras voice warnings that everyone ignores until the workings of the plot prove them to be speaking the truth… a depressing development in the evolution of that breed of thriller. (Miller, 2017)

Perhaps if Hawkins had understood why her first novel was so structurally satisfying for readers—the power of including a meaningful thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, as well as a basic structure with a beginning, middle, and end—her second novel could have been saved.

Conclusion

Writers often bristle at the idea that they must do certain things. This paper is not suggesting that either of the two structural rules discussed in this essay—(1) a beginning, midpoint, and ending, and (2) a thesis, antithesis, and synthesis—must be followed in every piece of writing. Far from it. Experimental writing is the mainstay of most literary criticism and creative writing workshops, and structural innovation in literature can produce important messages about art and humanity that extend beyond measures of simple reader satisfaction. That said, writers of commercial fiction—such as those in the crime and thriller genre—would benefit from knowing the science behind why certain story structures satisfy readers. Like Picasso, who first studied and mastered traditional visual art before breaking the rules, crime and thriller authors should first understand and master satisfying storytelling fundamentals before moving to experimentation.

Works Cited

Articles and Book Chapters

Boonstra, E.A. and Slagter, H.A. (2019) ‘The Dialectics of Free Energy Minimization’, Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 13(42), pp. 1-17.

Friston, K. (2010) ‘The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory?’, Nature Reviews: Neuroscience, 11, pp. 127–138.

Kornbluh, A. (2020) ‘Extinct Critique’, The South Atlantic Quarterly, 119(4), pp. 767-777.

Lin, P.-Y. et al. (2013) ‘Oxytocin Increases the Influence of Public Service Advertisements’, PLOS ONE, 8(2), p. e56934.

Lyons, R. (2017) 'Book Review: Into the Water by Paula Hawkins', Renee Reads Books. Available at: https://reneereadsbooks.wordpress.com/2017/07/21/book-review-into-the-water-by-paula-hawkins/ (Accessed: 11 March 2022).

Miller, L. (2017) 'She Was Right All Along: Paula Hawkins tries to create a formula in her follow-up to The Girl on the Train', Slate. Available at: https://slate.com/culture/2017/04/paula-hawkins-into-the-water-follow-up-to-the-girl-on-the-train-reviewed.html (Accessed 11 March 2022).

McDermid, V. (2017) ‘Into the Water by Paula Hawkins review – how to follow Girl on the Train?’, The Guardian, 26 April. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/apr/26/into-the-water-paula-hawkins-review (Accessed 11 March 2022).

Overbey, E. (2019) ‘The Twenty-Five Most-Read Archive Stories of 2019’, The New Yorker, online. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/2019-in-review/the-top-twenty-five-most-read-archive-stories-of-2019 (Accessed 11 March 2022).

Pennington, N. and Hastie, R. (1992) ‘Explaining the evidence: Tests of the Story Model for juror decision making’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62(2), pp. 189–206.

Pinker, S. (2007) ‘Critical Discussion: Toward a Consilient Study of Literature’, Philosophy and Literature, 31, pp. 161–177.

Pruitt, T. (2022) ‘Engaging the Science of Storytelling in Archaeological Communication’, in: Kapsali, P. and Phillips, R. (eds), “Aesthetics, Sensory Skills, and Archaeology,” Archaeological Review from Cambridge, 37(2).

Sayers, D. (1958) ‘The Unsolved Puzzle of the Man with No Face’, in A Treasury of Sayers Stories. Reprint, Project Gutenburg, 2011. Available at: https://gutenberg.ca/ebooks/sayersdl-treasury/sayersdl-treasury-00-h-dir/sayersdl-treasury-00-h.html (Accessed 11 March 2022).

Schnitker, S.A. and Emmons, R.A. (2013) ‘Hegel’s Thesis-Antithesis-Synthesis Model’, in: Runehov, A.L.C. and Oviedo, L. (eds), Encyclopedia of Sciences and Religions. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 978–978.

Seel, N.M. (ed.) (2012) ‘Cognitive Dissonance’, Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 588–588.

Speer, N.K. et al. (2009) ‘Reading stories activates neural representations of visual motor experiences’, Psychol Sci., 20(8), pp. 989–999.

Tooby, J. and Cosmides, L. (2001) ‘Does Beauty Build Adapted Minds? Toward an Evolutionary Theory of Aesthetics, Fiction and the Arts’, SubStance, 30(94/95), pp. 6–27.

Wilson, E.O. (2005) ‘Foreword from the Scientific Side’, in Gottschall, J. and Wilson, D.S. (eds) The Literary Animal: Evolution and The Nature of Narrative. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, pp. vii–xi.

Zak, P. (2013) ‘How Stories Change the Brain’, Greater Good Magazine: Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley, 17 December. Available at: https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_stories_change_brain (Accessed 11 March 2022).

Zak, P. (2014) ‘Why Your Brain Loves Good Storytelling’, Harvard Buisiness Review, 28 October. Available at: https://hbr.org/2014/10/why-your-brain-loves-good-storytelling (Accessed 11 March 2022).

Zak, P. (2015) ‘Why inspiring stories make us react: the neuroscience of narrative’, Cerebrum, 2(2). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4445577/ (Accessed 11 March 2022).

Zak, P. (2020) ‘Neurological Correlates Allow Us to Predict Human Behavior’, The Scientist Magazine. Available at: https://www.the-scientist.com/features/neurological-correlates-allow-us-to-predict-human-behavior-67948 (Accessed: 25 January 2022).

Books

Archer, J. and Jockers, M. (2016) The Bestseller Cod3. United Kingdom: Penguin Random House UK.

Aristotle (1996) Poetics. Translated by Malcom Heath. London: Penguin Books.

Brown, D. (2009) The Da Vinci Code. London: Corgi.

Cron, L. (2012) Wired For Story. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press.

Gottschall, J. and Wilson, D.S. (eds) (2005) The Literary Animal: Evolution and The Nature of Narrative. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Hawkins, P. (2015) The Girl on the Train. London: Penguin Random House UK.

Hawkins, P. (2017) Into the Water. London: Penguin Random House UK.

Jackson, S. (1946) The Lottery. Reprint, Iowa: Perfection Learning (Tale Blazers: American Literature), 1990.

James, E.L. (2012) Fifty Shades of Grey. London: Arrow.

Pinker, S. (1997) How The Mind Works. New York: W.W. Norton.

Poe, E.A. (1846) The Cask of Amontillado. Reprint, London: Amazon, 2022.

Yorke, J. (2013) Into the Woods: How Stories Work and Why We Tell Them. Milton Keynes: Penguin Random House UK.

Other Sources

Bavidge, J. (2022) ‘Modernism and Mystery: Experiments in Narrative’ [Lecture]. Institute of Continuing Education: University of Cambridge, 21 February.

BookMarks (2022) 'Into the Water: Paula Hawkins', BookMarks: Literary Hub [Review Aggregator]. Available at: https://bookmarks.reviews/reviews/into-the-water/ (Accessed: 11 March 2022)

CliffsNotes (2022) Summary and Analysis: ‘The Cask of Amontillado’ [Book Summary]. Available at: https://www.cliffsnotes.com/literature/p/poes-short-stories/summary-and-analysis/the-cask-of-amontillado (Accessed: 11 March 2022).

Cron, L. (2014) 'Wired for story: Lisa Cron at TEDxFurmanU', TEDxTalks [Lecture]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=74uv0mJS0uM (Accessed: 18 January 2022).

Wilson, R. (2022) ‘Critique: Its Critics and Their Critics’ [Lecture]. English Faculty: University of Cambridge, 8 February.